As experts in our subjects, it’s easy for us to overlook the processes which novices must undertake in order to get to the desired end goal. After returning from online learning last year, my team’s focus has been on improving our use of guided practice, the main element of face-to-face teaching we felt our pupils had missed-out on.

Why should we be talking about guided practice?

Increase fluency:

The main aim of guided practice is to create fluency (or make new processes automatic). As suggested by Barak Rosenshine’s research, showing pupils new information, or even modelling new processes to them, does not ensure a secure understanding. In order for pupils to transfer new processes from their short term memory into their long term memory, they must practice the process themselves over an extended period of time.

Increase independence:

Using guided practice also increases pupil independence by setting them up for success when completing longer tasks by themselves. Practice makes permanent, so the more practice we guide our pupils through, the better.

Success = motivation:

With guided practice, pupils have increased opportunities to be successful. Even, and especially, when the new process is difficult, the teacher is there with them, talking them through the next step and catching misconceptions before they can become embedded. The feeling of success felt by pupils is what makes them intrinsically motivated to continue their learning journey. Rosenshine writes, in his Principles of Instruction, that, ‘Teachers who spent more time in guided practice and had higher success rates also had students who were more engaged during individual work at their desks.’ Success breeds motivation, and that evidence seems as good a reason as any to buy-in to the concept of guided practice.

What is guided practice?

Guided practice is the stage between showing pupils a model, and directing them to complete a task independently. It is a teacher-led transitional phase where you want to be leading pupils through the task step-by-step, thereby reducing their cognitive load and being able to quickly address misconceptions.

The ‘I do, we do, you do’ approach to gradually reducing support for pupils is a really helpful idea, but in my experience it is often applied as a linear process and used to simplify what is a complex part of teaching. Guided practice is a non-linear phase. It can’t be done just once and isn’t a tick-box lesson element. It’s something we want to use for lots of separate new tasks, repeatedly, over a long period of time.

In this excellent blog from 2018, Harry Fletcher-Wood directs us to think about all those who are somewhere in between on the novice-expert continuum when he writes, “Experts and novices think differently – and those who are no longer novices but not yet experts think differently again.”

Novices are those new to a topic or task, who may know isolated pieces of information but whose wider knowledge of this area is lacking and therefore can’t make connections. If they try to do a new task independently, they will be at high risk of failure. We should not be directing novice pupils to just ‘have a go’ at a new task, because they will be unsuccessful and therefore less motivated to try it again.

Conversely, experts are those who are knowledgeable about the content of a topic and have practiced it multiple times, successfully. When they come across new pieces of information, they can fit them into what they already know, developing their schema. Schema are ways in which your brain organises information. Many of the thinking processes which experts go through are now subconscious.

What’s really important to be aware of is that there’s a lot of space on this continuum between novice and expert. And as Harry writes, those intermediates ‘think differently again’. Intermediates start to make connections between things, they start to develop those schema, those ways of organising their thoughts, but they are so at risk of failure and that makes them less motivated to try again. When planning lessons, we must remember that assumed knowledge is dangerous; we are, on a daily basis, at risk of alienating our pupils if we move too quickly to see them as experts and don’t guide them through this intermediate phase.

This example applied to knowledge of Lady Macbeth represents the difficulties which novices have observing and making links which experts make with ease:

How can guided practice be used in the English Literature classroom?

In our department we’ve broken our approach down into 6 steps.

1. Separate content and processes

As teachers, we must separate content and processes in the guided practice part of analysing literature.

Content is retrievable knowledge which must be secure (already in pupil’s long term memory) . If a pupil tries to hold new content in their working memory whilst trying to apply a new process, they will experience high cognitive load. Secure content knowledge relies on effective use of retrieval practice, for which I recommend the work of Kate Jones and Chris Curtis.

For example, pupils already need to know that Lady Macbeth obsesses over washing hands, and know that blood on hands is an image synonymous with guilt, before we can ask pupils to write an analytical para about Lady Macbeth’s guilt.

Other examples of content and processes include:

| Content | Process |

| – Plot – Character – Quotations – Word meanings – Allusions E.g. Recalling Lady M. says, ‘Out, damned spot!’ She is referring to blood on hands. Blood is synonymous with guilt. | – Identify methods – Analyse effect on reader/audience – Link moment to whole-text structure – Construct a paragraph/essay E.g. Responding to a Q Lady M. refers to the motif of blood when she says, ‘Out, damned spot,’revealing her admission of guilt to the audience. |

2. Identify implicit processes

The step that often seems to get missed within the ‘we’ section of ‘I do, you do, we do’ is the teacher articulating how and why they know what to do next. During guided practice, we have to try to strip back our thinking processes to the point a novice can follow them. That’s really difficult.

In selecting which implicit processes we need to articulate, it’s important to pool ideas with our colleagues about those pupils seem to find tricky. Things we’ve found useful for this are cross-subject lesson drop-ins and coaching. Sometimes it’s easier to see if an implicit process hasn’t been articulated clearly if you’re a non-subject specialist.

Examples of processes which can be articulated during guided practice in the Literature classroom are those where pupils have to apply their content knowledge, including:

- Identify key word in question

- Select methods in quotation

- Analyse effect on reader/audience

- Link moment to whole-text structure

- Make connections between author’s purpose and context

- Construct a paragraph/essay

- Choose appropriate verbs to show nature of author’s action

3. Script processes

Once you have identified those implicit processes, it’s so important to take time to break down what you do fluently into each separate part so that a novice can track your steps. This is also something best done collaboratively with a colleague so you can challenge each other’s thinking process.

If you don’t script the steps to use in your guided practice sessions, you will inevitably skip a step which you do subconsciously and this will result in losing some of your most novice pupils.

After using your script aloud for the same process a few times, you will – no doubt – begin to narrate these steps automatically. But, in the meantime, stick to your script.

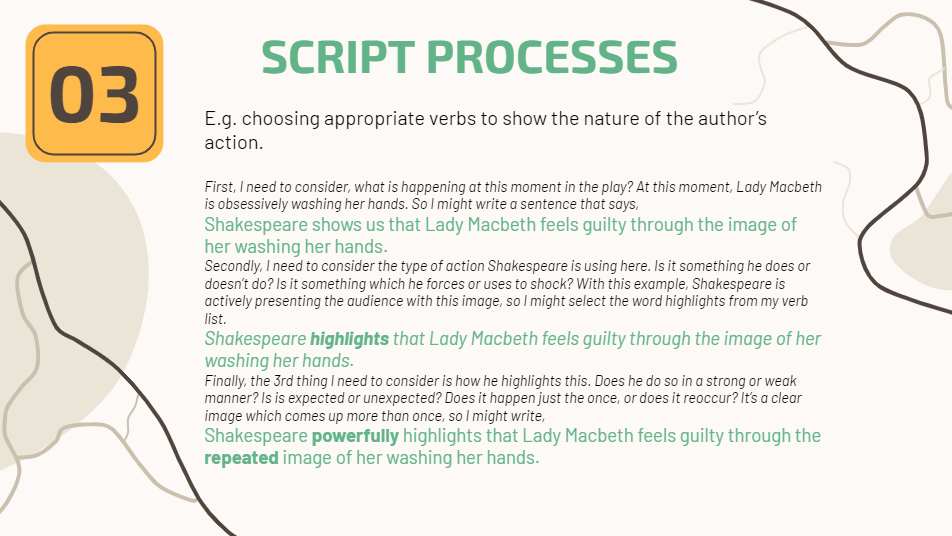

I might plan a script for the process of choosing appropriate verbs to show the nature of the author’s action. The pupils have their own lists of academic adverbs and verbs which I and they will refer to during this process. I will write this in advance, practice it myself aloud, and then read from this as I write under the visualiser to complete my model.

Having done this once as a model, I will do this again, this time with the pupils contributing to upgrading the verb choices, and again with them writing on mini-whiteboards, again in books, and so forth. It’s only one tiny process with three main steps but by articulating the steps which I go through again and again in the same format, pupils will start to develop fluency.

4. Provide scaffolds

Scaffolds are tools which support pupils to complete a task. They include physical resources but also, and more helpfully, frameworks which pupils can use to organise their knowledge.

Common choices might include sentence starters or gap fill activities. However, these don’t guide the pupils through the full thinking process they will later be expected to do independently.

We’ve moved to use of scaffolds that support pupils to identify the implicit processes themselves as they move through the implicit stage. Examples of this include a sheet which includes the building blocks of critical statements, which we call our ‘create a critical argument’ sheet. This is where they would find examples of adverbs and verbs as I previously referred to in my example script.

By guiding pupils step by step through these processes, we can support them to make connections across their schema, applying content through the processes to produce desired outcomes.

We have also found the use of the ‘What? How? Why?’ framework a helpful scaffold, both for questioning and guiding writing. Andy – who tweets @_codexterous – has written an excellent blog post which is really useful if you would like to try using these types of questions in your own classroom or department.

5. Chunk practice

In order to increase the success rate for pupils, and maintain pace, we ideally want to use guided practice for a short time focusing on a small, isolated process or element of a process. Chunking helps us to reinforce individual steps which can be put together later on, once they are automatic, to reduce cognitive load.

This can feel trickier in English than many other subjects; we’ve learnt a lot from other departments about how to do this more effectively, particularly maths and languages, and it remains a focus for us.

6. Use flexibly

In a video created for the Teach First ECF programme, Claire Stoneman says, ‘There is no one size fits all solution’ to guided practice. It isn’t something to just be used within one lesson one time; it should be used repeatedly for the same processes over and over.

It’s important to remember that our pupils will be novices in many different domains, even if they are experts in others. A pupil’s journey from novice to expert won’t be linear. Sometimes pupils will return to the novice stage if they are out of practice and we have to guide them along the path towards intermediate again. That’s okay and to be expected.

We as teachers need to use our professional judgement and feedback from pupil work to assess their current position on the pathway to help them make their next steps.

This is an approach which we think can be mapped onto a whole curriculum or onto a shorter sequence of lessons, and which works for English Language as well as Literature. Creating and refining these 6 steps has been a real process for us and it remains something we’re working on, so feedback is certainly welcome!